Hardcover, paperback, eBook

and audiobook available in

stores and online.

Buy now at:

Amazon.com

Barnes & Noble

IndieBound

iBookstore

It sounds preposterous, but Jon Reiner, the James Beard-winning food writer who penned Esquire's "How Men Eat" series, was once himself unable to eat.

Debilitated by complications from Crohn's disease, the "bizarre strain of steerage-class masochism" that causes the immune system to friendly-fire attack its own gastrointestinal tract, the New Yorker was forced by his doctors to adopt an NPO (from the Latin nil per os, or "nothing by mouth") lifestyle, hooking his deteriorating body up to an automated food pump in the hopes his excruciating symptoms would abate.

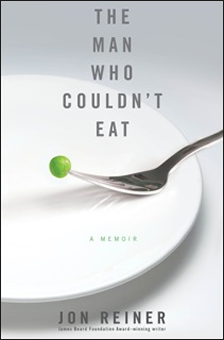

Expanding on a 2009 Esquire article, Reiner's The Man Who Couldn't Eat (Gallery, Sept. 6) knocks the conventional food memoir on its bloviated head, chronicling with tremendous passion and candor what it's like to waste away — and what it's like to come back.

While the pages of many epicurean remembrances are swollen with engorged passages about mystical meat or wisdom whispered across a gnocchi board, The Man Who Couldn't Eat deals with shit differently. That's meant in a literal sense — most food writers shy away from anything even resembling a digestive reference, careful not to turn readers' stomachs. But Reiner is honest about his violent disease, which hospitalizes him numerous times and leads to his band of avuncular physicians branding him an NPO candidate. The damage of the extreme medical decision lingers even after he's permitted to take food and drink orally again. "I am an empty vessel into which the last hope for healing is being spooned," writes Reiner, "only to pass unnoticed and flood out as unstoppable diarrhea."

It's cruel that Reiner, so food-fixated he's able to rattle off every dish that appears on-screen in the movie Moonstruck, is forced to view eating as "fickle medicine." Nowhere is this more apparent than during his post-hospital at-home ordeal, hooked up to an intravenous feeding pump ("like living in a blender") as his worried wife and two young children carry on as normally as they can. Since the sight of their sickly dad upsets his sons, Reiner chooses to excuse himself from the family dinners he'd always held in such meaningful regard ("mealtime now comes with regular servings of separation anxiety"). Patching us in to his internal monologue as he attempts to stimulate atrophied taste buds by licking the salt off a fry or huffing the perfume from a bag of dried apricots, Reiner takes us on a Diving Bell and the Butterfly-style ride, his every outside-the-glass craving turned self-destructive by his body's betrayal.

Reiner's vivid remembrances of food — childhood trips to Katz's Deli on the Lower East Side, emancipating vacations in Maine, hot empanadas in the park with his boys — are scattered with quiet symmetry across the expanse of Reiner's nightmare. Though the interminable disposition of his struggle to return to the land of the eating leads to overblown description in spots, The Man Who Couldn't Eat is unlike any food memoir you've ever read.

"Unlike any food memoir you've ever read."